Joel

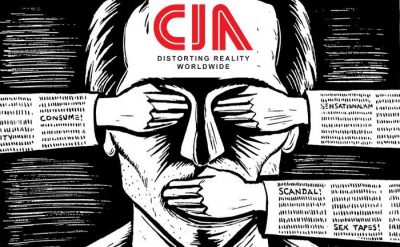

Whitney is a co-founder of the magazine Guernica, a magazine of

global arts and politics, and has written for many publications,

including the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. His book Finks:

How the C.I.A. Tricked the World's Best Writers describes

how the CIA contributed funds to numerous respected magazines during

the Cold War, including the Paris Review, to subtly promote

anti-communist views. In their conversation, Whitney tells Robert

Scheer about the ties the CIA’s Congress for Cultural Freedom had

with literary magazines. He talks about the CIA's attempt during the

Cold War to have at least one agent in every major news organization

in order to get stories killed if they were too critical or get them

to run if they were favorable to the agency. And they discuss the

overstatement of the immediate risks and dangers of communist regimes

during the Cold War, which, initially, led many people to support the

Vietnam War.

James

Jesus Angleton was part of this post-OSS group

that understood how important spying and covert ops had been in World

War II. And from there, he makes all kinds of terrible mistakes. He

and his group believed essentially that they needed to do better

propaganda than the Soviets did, and one of the ways that they

thought they could do it better was to do it subtly and, you could

say, secretly.

So,

when this program is threatened with exposure in ‘64, ‘65, ‘66

and ‘67 through various sources like Ramparts and The New York

Times, this privilege of secrecy that they enjoyed was not something

that they were willing to give up. So you have something that is

described as relatively benign, this funding of culture through the

Congress for Cultural Freedom, a funding of student movements through

the National Student Association, the funding of labor unions that

would be less communist-influenced than the communist-dominated ones

that they presumed were out there. These were seen as benign answers.

They were reactions to Soviet penetration. So, secrecy is a key to

making them work.

So,

even if you want to make the argument that, for instance, the

Congress for Cultural Freedom never censored its magazines–which I

think has been severely disproved; they did censor. Even if you

wanted to say that they published all sorts of great writers–which

clearly they did; that was part of the subtlety of it and part of the

brilliance of it, and part of the soft-power charm of it. Even if you

wanted to say all that, when the secrecy is exposed by honest

accounting in the media, the fourth estate, the adversarial media of

American bragging around the world, they are so attached to their

secrecy, and so upset, the CIA group led by people like Angleton,

that they commit something that is about as anti-American as anything

in our system. Which is: more secrecy, more media penetration to the

point of penetrating, first, the anti-Vietnam War press; second, the

student, the college student newspapers and press; the alternative,

so-called, press. Which essentially is a license to do what they did

later. So, where Ramparts was penetrated, leads to Operation Chaos,

presumably; that leads to Operation Mockingbird in the seventies.

By

the time we have Carl Bernstein reporting on Operation Mockingbird,

and John Crewdson reporting on its international equivalent in the

New York Times–Bernstein in Rolling Stone–you essentially see the

CIA trying to have at least one agent at every major news and media

organization it can do in the world.

And

Crewdson reporting in the Times at the end of 1977 essentially says

that they had one agent or contract agent at a newspaper in every

world capital on Earth. They could get stories killed or get stories

to run that portrayed the CIA’s views in a favorable way, or kill

them if they did not.

Comments

Post a Comment